genotyping is sometimes also undertaken for the

purposes of clinical epidemiology and hospital infec-

tion control (Pfaffer and Herwaldt 1997).

Acute phase response

The acute phase response is a group of nonspe-

cific, cytokine-mediated phenomena that occur in

response to inflammation (Gabay and Kushner

1999). As shown in Table 9.2, one or more compo-

nents of the response may be present as a conse-

quence of infection. Which components are present

is determined by the set of cytokines characteristi-

cally generated during the infection. Bacterial infec-

tions, for instance, typically cause a wide variety of

cytokines to be released, resulting in all three of the

classical components of the acute phase response:

fever, neutrophilia, and increased plasma concentra-

tions of the acute phase proteins.

Both the acute phase protein reaction and neutro-

philia have been used as markers for bacterial infec-

tion. The acute phase proteins, C-reactive protein

and fibrinogen (usually measured using the ESR),

are often increased in bacterial infection but the

specificity of these markers, as would be predicted,

is quite low.

The neutrophilia that occurs as part of the acute

phase response is due largely to the release of

mature neutrophils held in reserve in the marrow

sinusoids, but slightly immature cells, band neutro-

phils, may also be released. Neutrophilia is demon-

strated by an increase in the neutrophil count. The

neutrophil count is the concentration of neutrophils

in whole blood. The neutrophil count is often called

the

absolute

neutrophil count to distinguish it from

the neutrophil fraction as reported in a white cell

differential. Because neutrophils make up a large

fraction of the white cells in circulation, an increase

in neutrophil count usually produces an elevation in

the white cell count. Increased white cell counts are

not inevitable, however, and increased neutrophil

counts can be found in some infected patients who

have normal white cell counts (Ardron et al. 1994).

Neither the neutrophil count nor the white cell count

are highly sensitive markers of bacterial infection.

This is not surprising as the range of tissue damage

and extent of systemic response caused by

infections, even infections with the same pathogen,

vary so greatly among patients. The neutrophil

count may be somewhat more specific than the white

cell count in some clinical settings (Gombos

et al.

1998). Because band neutrophils may be released

as part of the acute phase neutrophilic response, the

measurement of the band neutrophil count has also

been used as a marker of bacterial infection (Novak

1993). The quantification of band neutrophils is

even incorporated into most automated blood cell

counters. Despite its appeal, the band neutrophil

count is no more reliable as a marker of infection

than is the neutrophil count (Bentley

et al.

1987,

Ardron

et al.

1994).

The finding of neutrophils in body fluids being

evaluated for bacterial infection quite reliably

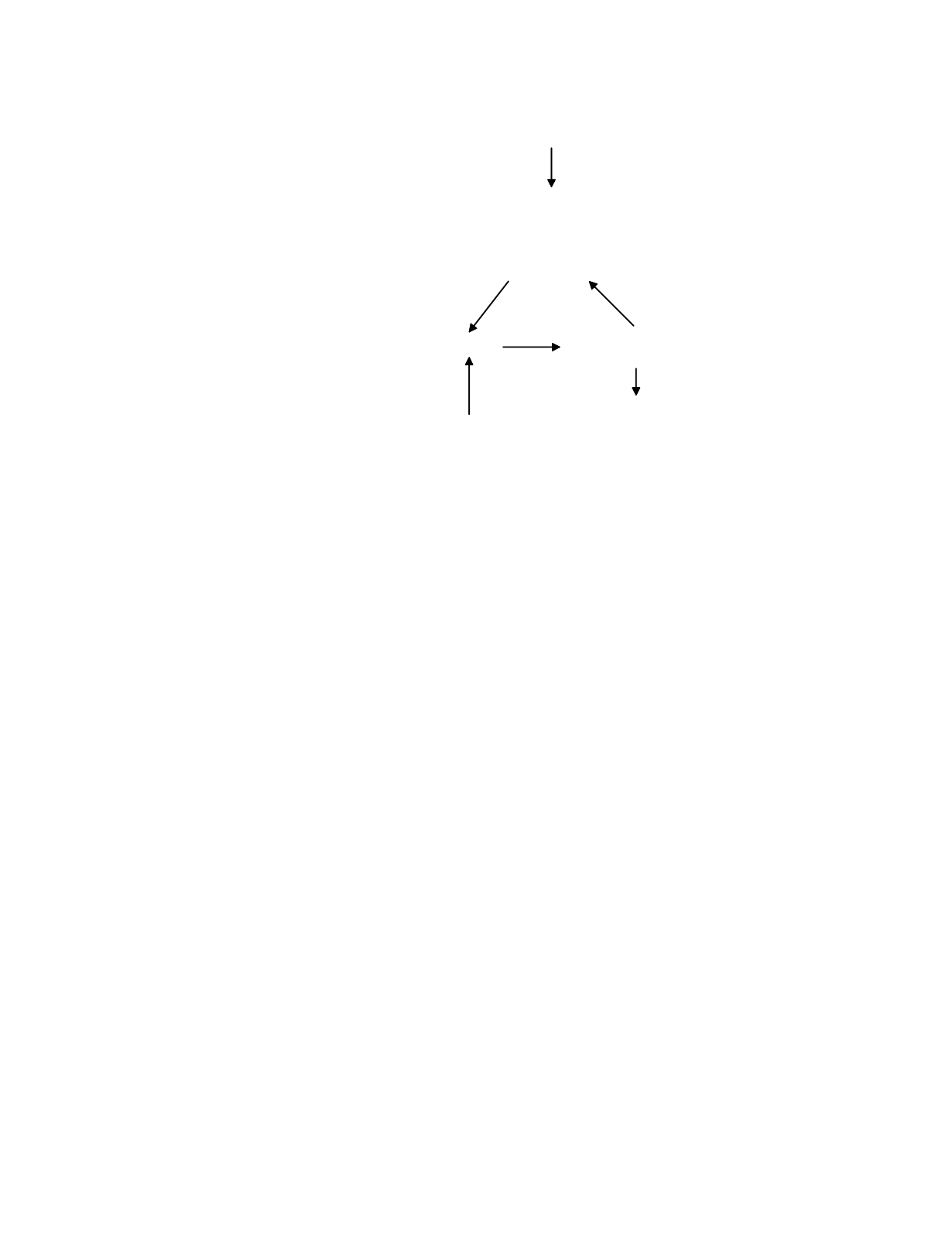

Tissue Injury

9-13

plasma

extracellular fluids

lymph

SITE OF

INFECTION

organism

proteins

nucleic acids

metabolic products

secreted products

LYMPHOID

TISSUE

antibodies

cytotoxic T cells

PLASMA AND

EXTRACELULAR FLUIDS

excreta

Figure 9.3

A model of the disposition of high specificity markers of infection.