CLINICAL USE OF LABORATORY STUDIES

Physicians select laboratory studies and interpret

the results. They integrate their laboratory interpre-

tations into the clinical assessment through the

synergistic interplay of quantitative analysis and

clinical judgment. This process, which occurs

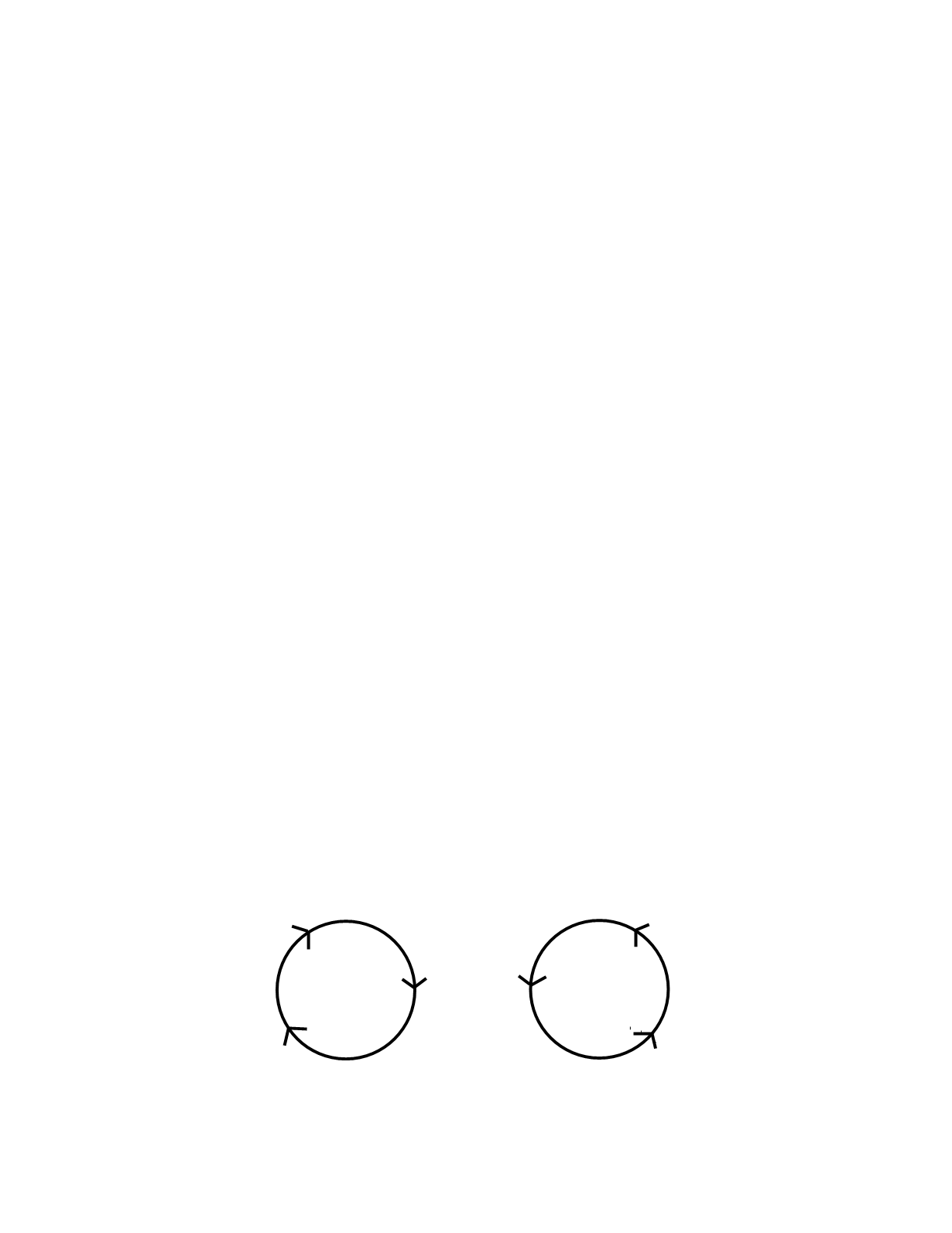

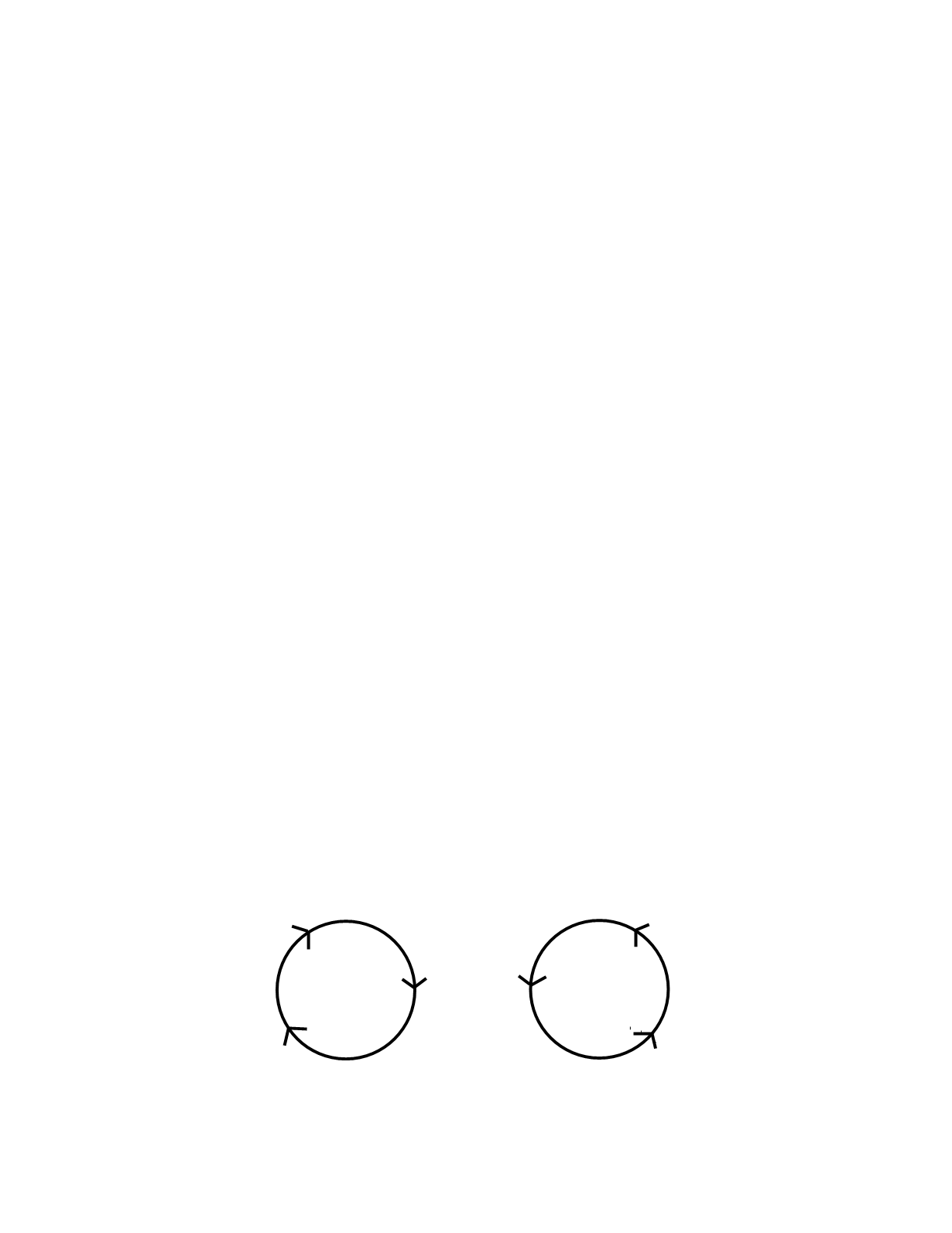

repetitively throughout the care of a patient (Figure

1.1) constitutes the general pattern of use of labora-

tory studies.

If a laboratory study is to provide clinically

useful information, it must be ordered with a

specific clinical goal in mind (Table 1.1). The clini-

cian relates each goal to a set of specific information

needs based upon a pathophysiologic understanding

of the disorder or disorders under consideration

(Table 1.2).

For example, one medical goal in a patient with

severe chest pain is to establish or exclude the

diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Infarction

means cell death so the foremost information need is

to determine if myocyte death has occurred. In

addition, though, the information needs might

include an assessment of cardiac function and

electrophysiology as infarcts typically cause regional

contractile dysfunction and impaired myoelectric

signal propagation in the ischemic myocardium.

Having identified the information needs for a

patient, the clinician then orders clinical and labora-

tory studies to address the needs, here also depend-

ing upon pathophysiologic principles to select and

interpret the studies. For instance, in pursuing the

question of cardiac myocyte death in the patient with

chest pain, the clinician will request that the plasma

concentration of creatine kinase-MB be measured

because there is a reliable pathophysiologic relation-

ship between the plasma concentration of this

enzyme and the presence of myocyte death.

The interpretations of the study results and of

additional clinical observations provide the input for

reevaluation of the clinical assessment and revision

of the catalog of medical goals for the patient. And

the cycle begins again.

This simple picture of study use does not,

however, take into account a number of real-life

considerations including (1) limitations in the avail-

ability of studies, (2) delays in the time it takes to

receive study results, and (3) the physical, psycho-

logical, and financial costs of performing studies.

When planning the laboratory evaluation of a

patient, the clinician must keep in mind the capabili-

ties of the clinical laboratories. Not every study is

available at every hospital. Fortunately, the

standards of medical care in developed countries are

so high that, usually, when a laboratory study is not

available, either an adequate substitute study is, or a

specimen can be sent to a reference laboratory, or

the patient can even be transferred to a medical

center that does offer the study. The availability of

laboratory studies can also be constrained by limita-

tions in the schedule for study performance—a study

that cannot be done when needed may be no better

Laboratory-based Medical Practice

1-1

Interpretation

of results

Laboratory

study results

Clinical

assessment

Interpretation

of observations

Clinical

observations

Selection of

laboratory studies

Selection of

clinical studies

Determination of

additional clinical

information needs

Figure 1.1

Cyclic structure of the use of medical studies.

Chapter 1

LABORATORY-BASED MEDICAL PRACTICE

© 2001 Dennis A. Noe