than a study that is not offered at all. Alternative

studies that can be obtained in a timely fashion must

then be used instead.

Another and more frequent consideration in

ordering studies is the time that elapses between

requesting a study and receiving the result. If the

wait is short, a study can be ordered and the result

received and interpreted prior to requesting the next

study, if additional testing is indicated. This is

sequential test ordering. It is efficient because each

study ordered contributes to clinical care and is cost-

effective because the number of studies ordered is

minimized. If the turnaround time is long, however,

the patient's care is compromised by the cumulative

delay in obtaining study results occasioned by

sequential testing. In that case most or all of the

potentially useful laboratory studies can be ordered

together and the results interpreted

en masse

. This

is concurrent ordering. It is not efficient but, when

properly used, is cost-effective since the costs of

delayed care are minimized. Concurrent ordering

must not be confused with the indiscriminate order-

ing of laboratory studies by those who have the

misconception that the greater the number of studies

ordered, the greater the amount of information that

will be available for use in the care of the patient.

Remember, data is not always information! Infor-

mative study results contribute to the care of the

patient. Superfluous study results, at best contribute

nothing to the patient's care, often obscure informa-

tive results, and sometimes even misinform.

Lastly, clinicians must keep in mind that labora-

tory studies are costly. The financial burden of

medical bills, especially outpatient bills, is in no

small part due to laboratory charges. In addition,

much of the physical and psychological discomfort

experienced by patients as part of their medical care

is attributable to the invasive nature of most labora-

tory studies. Although it is not always possible, it is

important to include cost as a consideration in study

selection.

EXPRESSING LABORATORY RESULTS

Most laboratory studies are simply measure-

ments. The information requested is of the type

"How much, or many, of some analyte is present in

this specimen?" As such, these studies quantify the

analyte of interest. The level of quantification

achieved varies depending upon clinical needs and

the sophistication of the method of measurement.

Qualitative studies are characterized by binary

quantification. The analyte is reported as either

"present" or "absent." Semiquantitative studies

arrange study results into grades or categories.

Results may, for example, be reported as "absent /

trace / moderate / marked" or "zone I / zone II /

zone III." Quantitative studies use a scale of

measurement. The scale is graduated according to a

reference measurement, called the unit of measure-

ment. The value of a quantitative measurement

indicates how many multiples of the reference

measurement, or unit, are contained in the specimen.

SI Units

There exists an international system of units, le

Systčme International d'Unités (abbreviated SI),

advanced by the International Committee of Weights

and Measures as the system of units to be adopted by

all signatories of the Diplomatic Convention of the

Meter, 1875 (Lehmann 1979). From this system

there has evolved a recommended system of units

(Recommendations 1978 and 1984) to be used in

medicine (Dybkaer 1978a; Dybkaer 1978b; Siggard-

Anderson

et al.

1987). These recommendations are

the product of the Clinical Chemistry Committee of

the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemis-

try (IUPAC) and the International Federation of

Clinical Chemistry. They are supported by the

International Committee for Standardization in

Laboratory-based Medical Practice

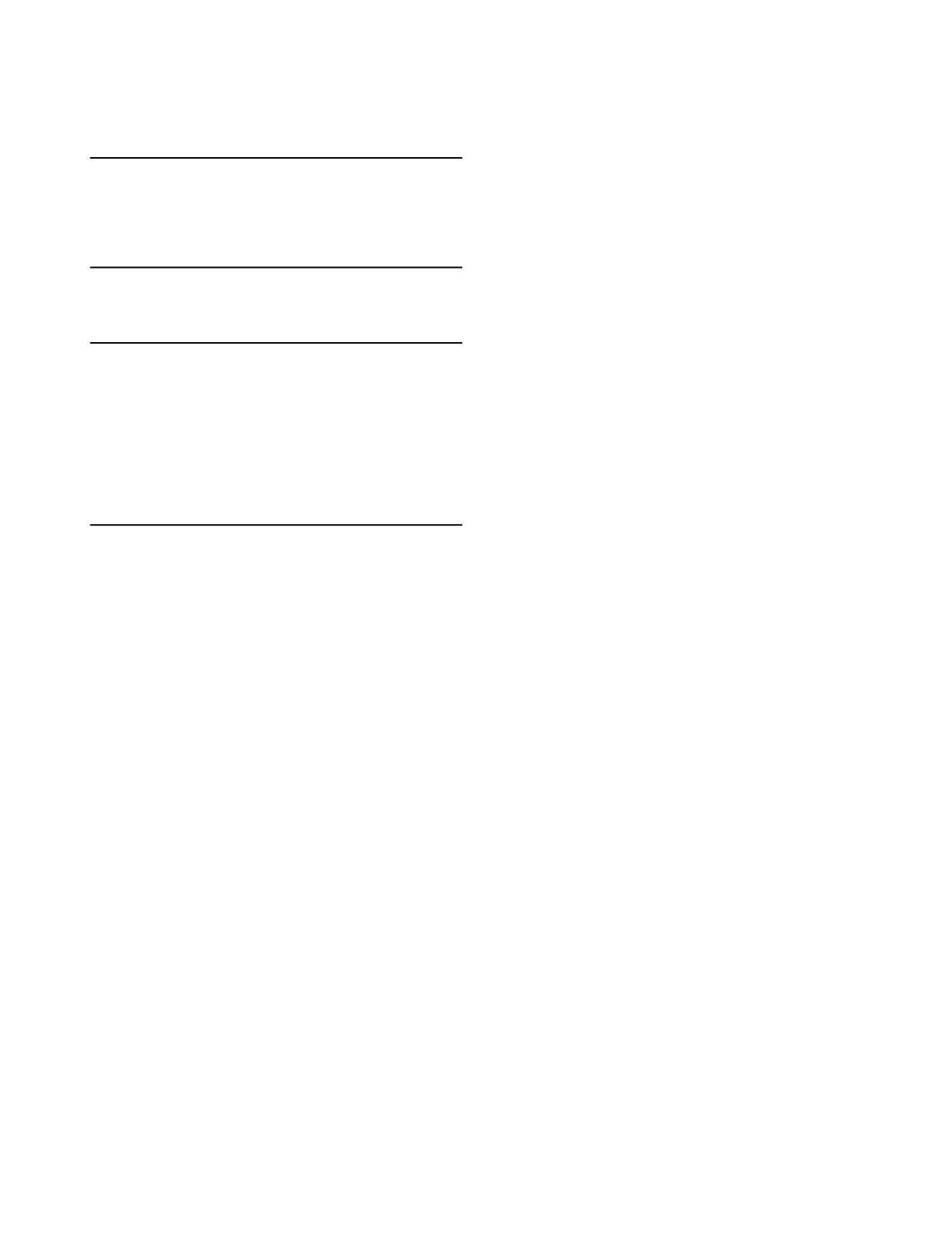

1-2

Table 1.1

Goals of Medical Care

1. Detect and quantify risk of future disease

2. Detect subclinical disease

3. Establish and exclude diagnoses

4. Assess disease severity and establish prognoses

5. Select appropriate therapy

6. Monitor disease progress and treatment effect

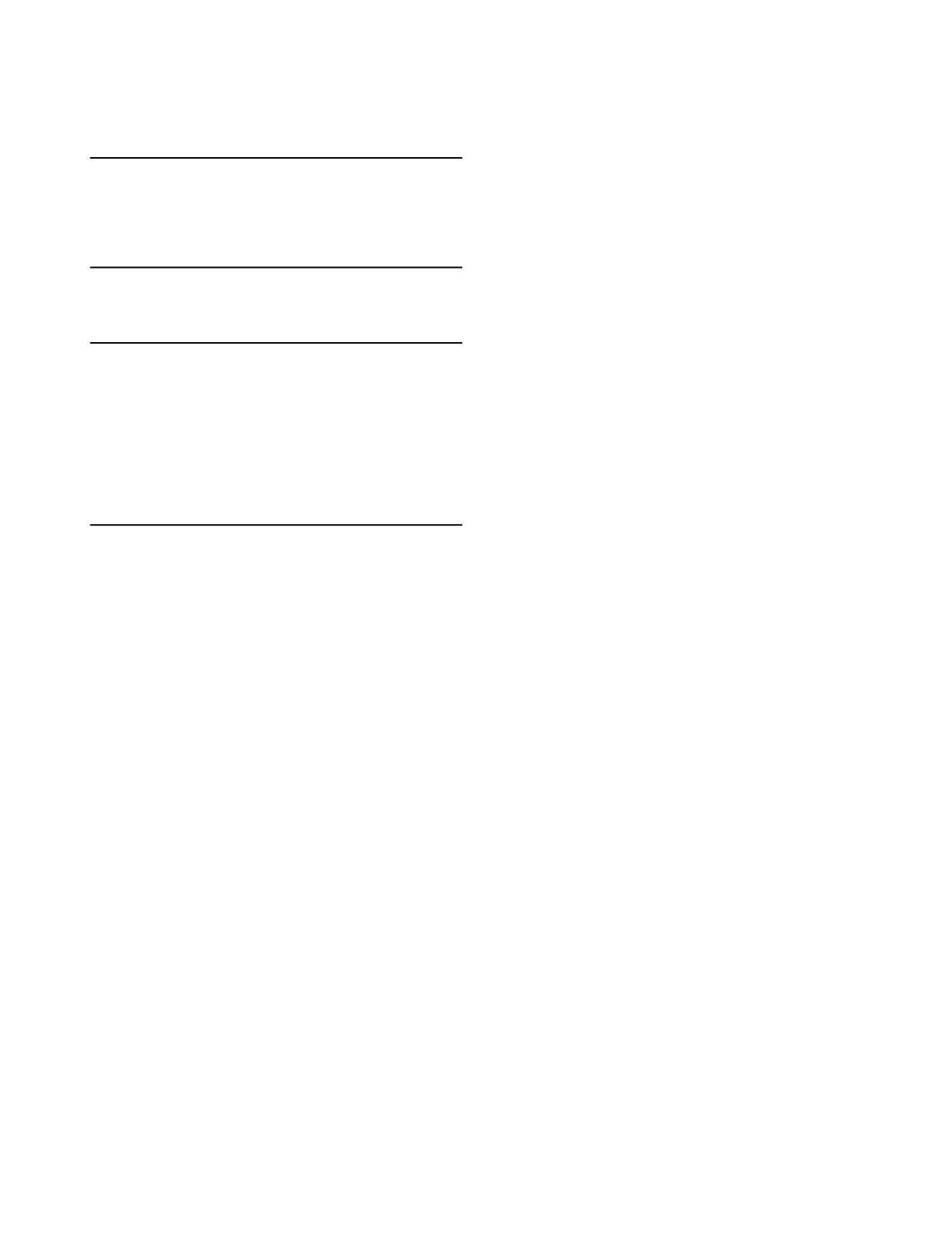

Table 1.2

Clinical Information Needs

1. Assess organ function

2. Assess metabolic activity

3. Assess macro- and micronutritional status

4. Detect and monitor neoplasia

5. Detect and quantify tissue injury

6. Detect and identify genetic disorders

7. Detect and identify immunologic disorders

8. Detect and identify infectious agents

9. Detect and identify intoxicants and poisons

10. Monitor therapeutic agents