A different way in which genetic alterations can

be used in the laboratory evaluation of cancer is to

detect a genomic change that is not abnormal in

itself but which indicates a monoclonal origin of the

tumor cells. The foremost example of this is in the

evaluation of lymphoid cancer where monoclonality

is revealed by demonstrating an identical V(D)J

rearrangement in all of the cancer cells. Homogene-

ity of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rear-

rangement is found in tumors of B lymphocyte

lineage, and of the T cell receptor

α

or

β

genes in

tumors of T cell lineage (Scarpa and Achille 1997).

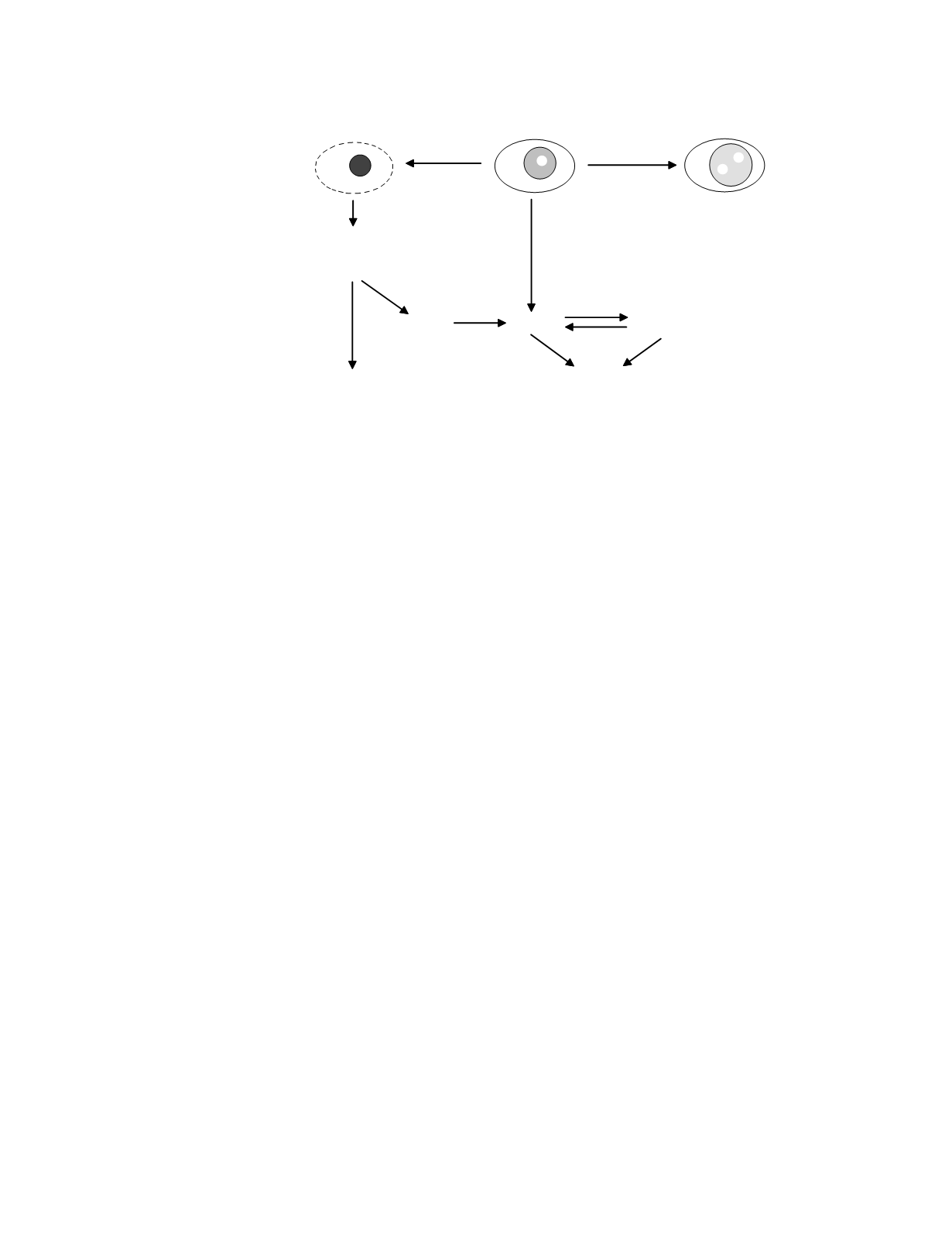

Marker substances.

The substances that serve

as markers for cancer originate in cancer cells and

enter the circulation following secretion from living

cells or release from dead cells (Figure 11.1).

Secreted substances enter the plasma directly and

distribute in the extracellular fluids. They are re-

moved by systemic processes. Substances that are

released from dead cells enter the extracellular space

in and around the tumor and are either catabolized

locally or are removed in the lymph. Lymph-borne

marker substances eventually enter the plasma,

distribute in the extracellular fluids, and are elimi-

nated. Marker substances released from cancerous

blood cells are unusual in that they have direct

access to the plasma. Marker substance concentra-

tions can be measured in any of the body fluids

transited by the marker substance. The most com-

monly studied fluid is plasma. Other fluids, such as

pericardial fluid and peritoneal fluid, are studied

when tumor involvement of the respective mesothe-

lial linings is suspected. Urine may be studied if the

marker substance or a metabolite of the substance is

eliminated by renal clearance; concentrations in the

urine are higher than in the plasma thereby allowing

for easy analyte measurement.

The concentration of a marker substance in the

plasma and extracellular fluids depends upon the rate

of entry of the substance into the fluids and its rate

of systemic elimination. Except in advanced

disease, when many body functions are compro-

mised, the systemic elimination of marker substances

is fairly constant. That means that the predominant

variable in the plasma concentration of marker

substances is the rate of entry into the body fluids.

For secreted substances, the rate of entry is deter-

mined by the individual cell rate of substance synthe-

sis and secretion and by the number of cells, i.e. the

size of the tumor. The individual cell secretion rate

usually varies from cell to cell within a tumor due to

the greater than normal degree of inter-cell pheno-

typic variability found in cancer. The rate also

varies depending upon where the cancer cells are in

their malignant evolution. Some marker substances

will be expressed in early in the evolution of the

cancer, when the cancer cells are fairly well differ-

entiated, and not later, when the cells show poor

differentiation. Other marker substances will be

expressed in poorly differentiated cancer cells and

not in well differentiated cells. Still other marker

substances will be expressed throughout the pheno-

typic evolution of the cancer.

For released substances, the entry rate is deter-

mined by the individual cell content of the marker

substance, by the number of cells, and by the

turnover rate of the cells. As with secreted marker

substances, released marker substances show

Cancer

11-4

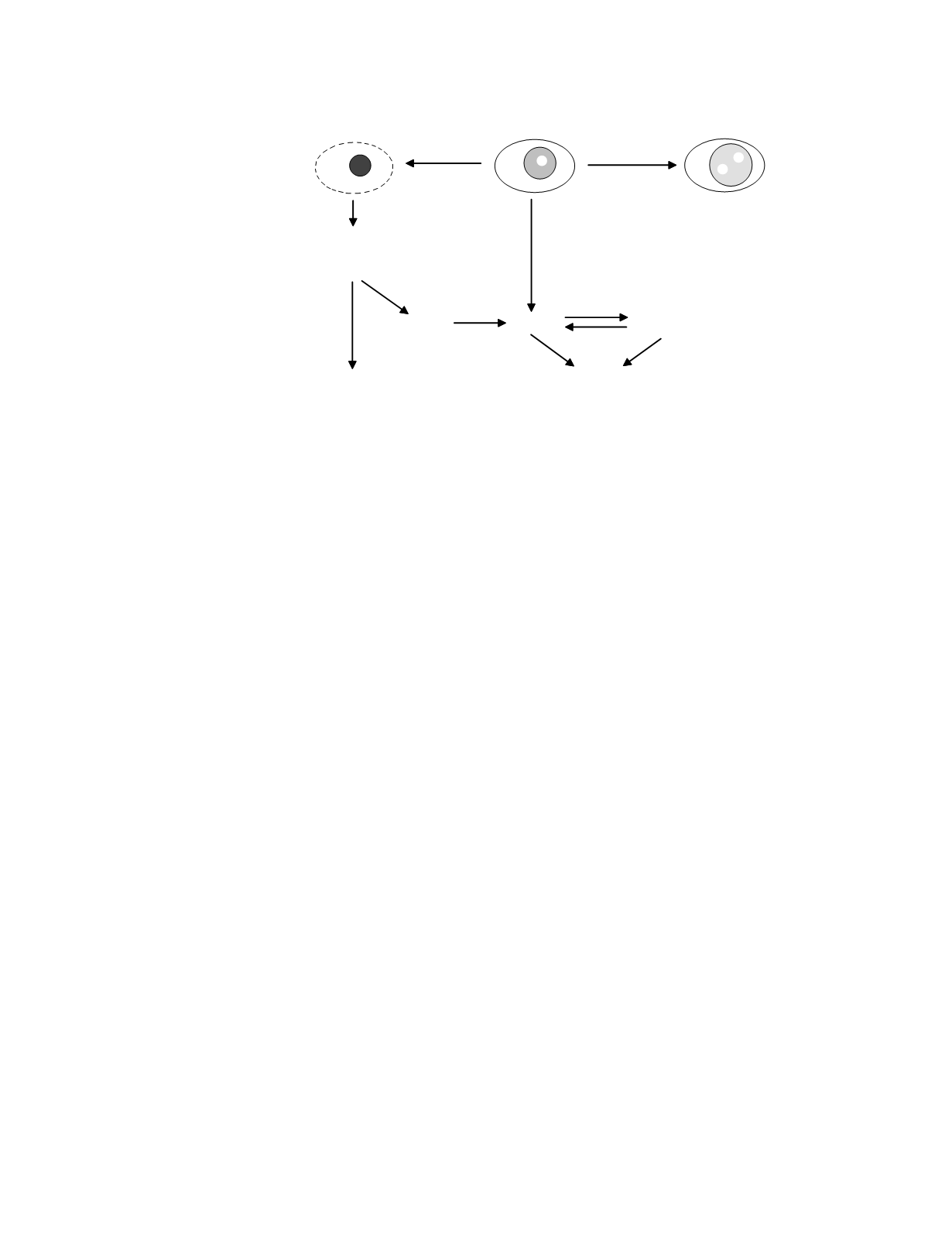

Figure 11.1

A model of the disposition of marker substances for cancer.

local

catabolism

plasma

extracellular

fluids

systemic

elimination

lymph

PLASMA AND

EXTRACELLULAR FLUIDS

LOSS

CANCER CELLS

death

clonal

evolution

loss of markers

new markers

local

extracellular

pool