future. As both of these uses for prognostication

represent exercises in clinical classification, it is

possible to describe the performance of prognostic

studies to a large extent using the same techniques

that have been developed to characterize diagnostic

classification.

In diagnostic classification, the fundamental

measures of performance are sensitivity and specific-

ity. Because there may be more than two prognostic

categories and because outcome and risk categories

are not necessarily as antithetical as the diagnostic

categories of disease and free from disease, terms

other than sensitivity and specificity need to be

employed to measure performance in prognostic

classification. Unfortunately, no distinctive terms

have been invented for this purpose. Instead, the

utilitarian phrase, fraction correctly classified, will

be used here to quantify the fraction of individuals

belonging to a prognostic group who are correctly

placed into that group by the results of the laboratory

study.

The prognostic group into which an individual is

classified is determined by the study result for the

individual and the study's critical values. When

there are only two prognostic categories, there will

be a single critical value. If the study result is

smaller than the critical value, the individual will be

assigned to one of the prognostic groups and if the

result is larger than the critical value he or she will

be assigned to the another. Because any study result

can potentially function as the critical value, the

comprehensive description of the classification

performance of the study requires a listing of the

fractions correctly classified for every possible

choice of critical value. This is conveniently done

graphically by means of a performance characteristic

curve, i.e., a ROC curve.

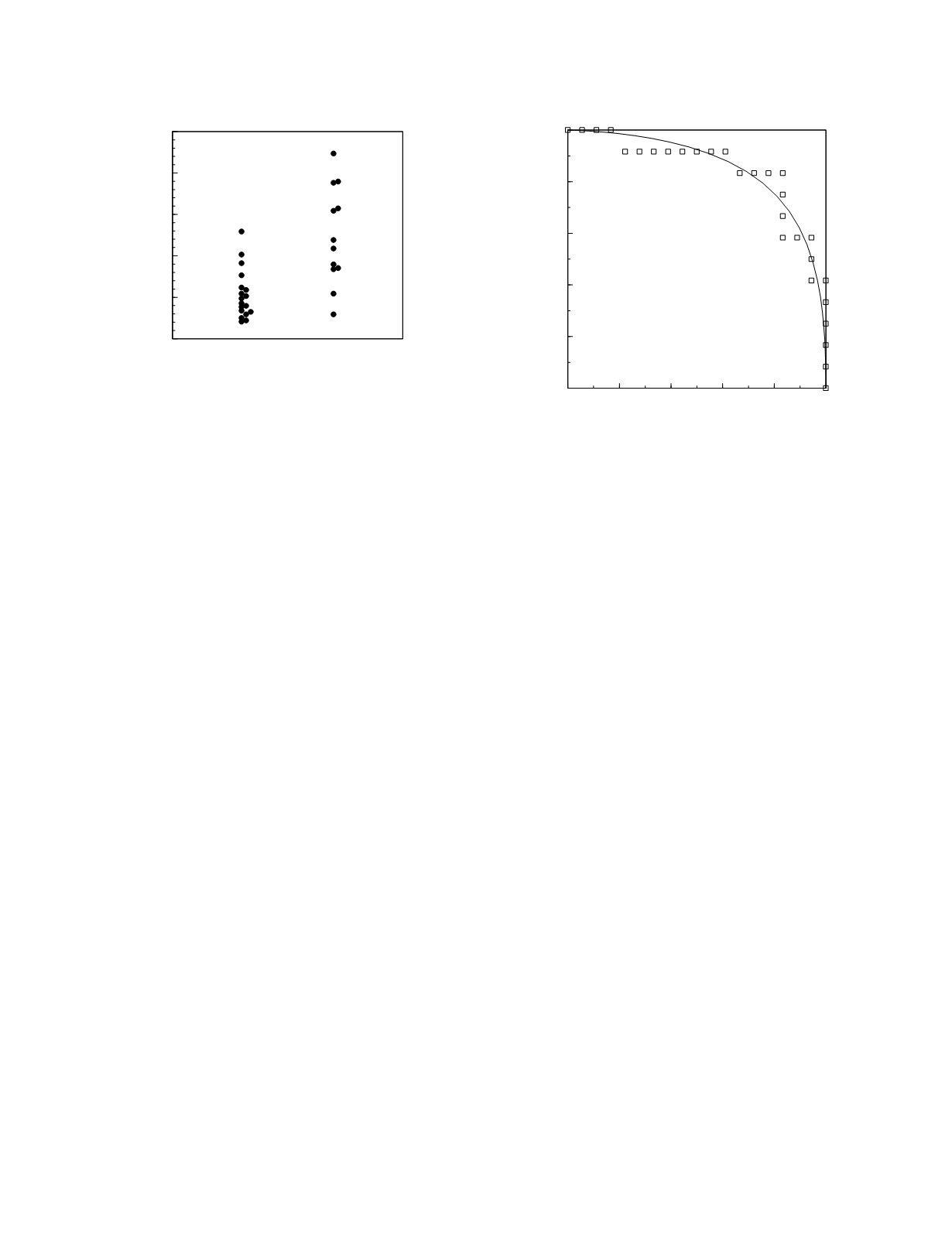

For example, in a study comparing the prognos-

tic performance of acetaminophen half-life and the

14

C-aminopyrine breath test as outcome predictors in

acute acetaminophen poisoning, Saunders

et al.

(1980) report the acetaminophen half-lives shown in

Figure 3.14. As pictured here, the good prognosis

group consists of those patients who had either no

liver damage or mild to moderate liver damage as a

consequence of the drug overdose. The poor

prognosis group is made up of those patients who

either died acutely or who had severe liver damage.

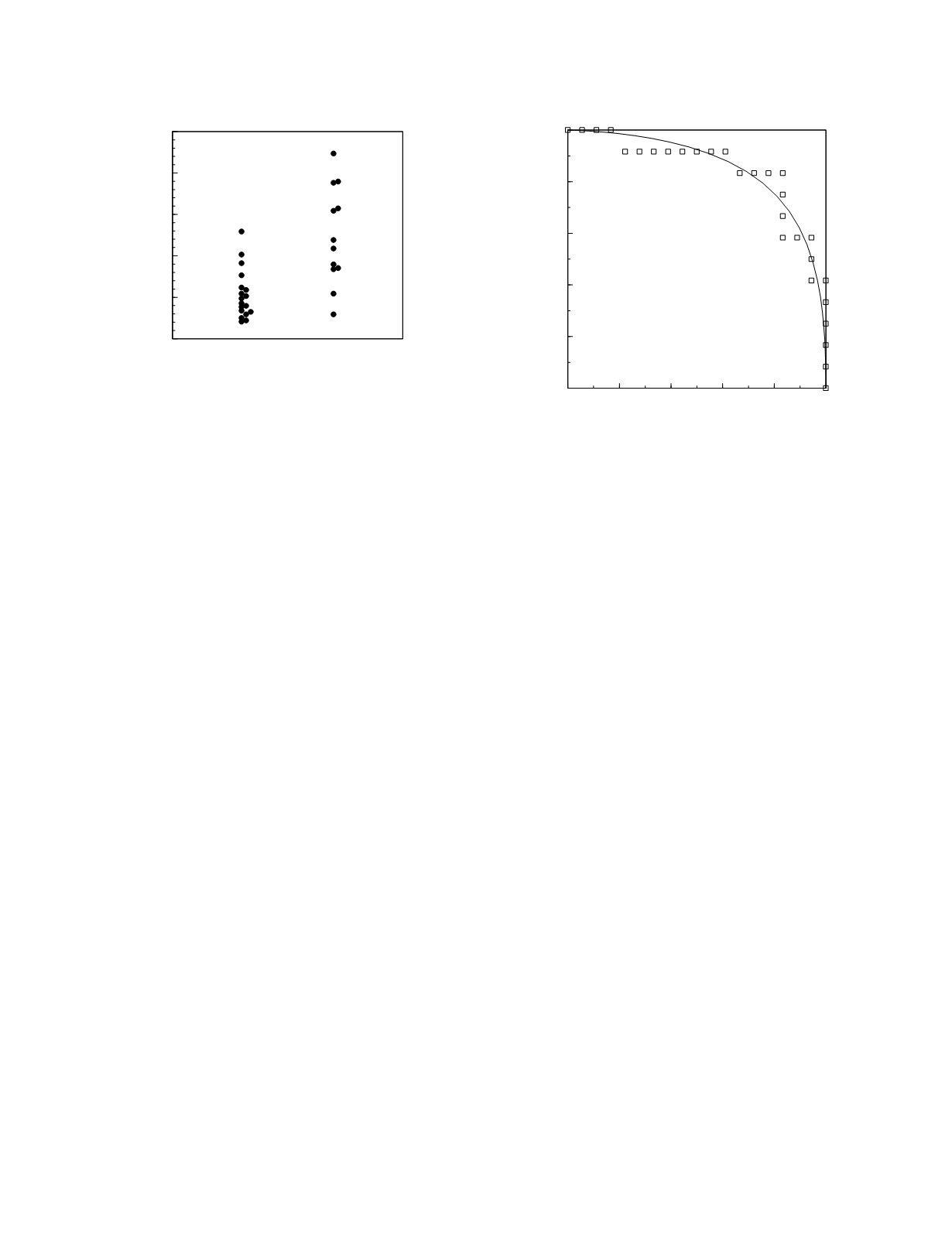

The ROC curve for these data is shown in Figure

3.15.

Multiple prognostic categories

When there are more than two prognostic

categories, more than one critical value is necessary;

the number being one less than the number of

categories. Hence, two values are required to

separate three categories: one value indicates the

separating line between the good prognosis group

and the intermediate prognosis group and the second

value delimits the intermediate and poor prognosis

groups. A complete description of the performance

of the study as a prognostic classifier in this case

requires tabulation of the fraction correctly classified

for each of the prognostic categories for every

Diagnostic and Prognostic Classification

3-16

Prognostic category

0

5

10

15

20

25

Acetaminophen half-life (h)

poor

good

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Fraction correctly classified

Good prognosis group

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Fraction correctly classified

Poor prognosis group

Figure 3.15

ROC curve for acetaminophen half-life. The

squares represent the points constructed from the observed

data. The continuous line is the curve constructed from

frequency distribution models of the data.

Figure 3.14

Individual values of acetaminophen half-life in

acute acetaminophen poisoning with data sorted into two

prognostic categories.