the earliest demonstration of the increase in CEA

concentration was achieved by the 1

3s

rule. This rule

gave a significant result 4 months prior to the clini-

cal appearance of the tumor recurrence and 3 months

prior to obtaining a significant result based on the

population-based critical value. Thus, for this

patient, the 1

3s

rule performed very well and would

have allowed for the earliest treatment of the

recurrence.

MONITORING THERAPEUTIC RESPONSE

The purpose of monitoring therapeutic response

is to determine if the expected benefit has been

obtained from a therapeutic maneuver and to gauge

the magnitude or risk of any unwanted effects from

the maneuver. Clinical observations may provide all

the information needed to assess the efficacy and

toxicity of medical therapy but, often, laboratory

studies are needed to supplement the clinical obser-

vations. Indeed, sometimes there are no overt clini-

cal findings that correlate in a timely fashion with

the effects of therapy, in which case laboratory

findings are the only useful measure of therapeutic

response.

Medical intervention is instituted with the inten-

tion of curing a disorder or decreasing the intensity

or extent of the disorder. Therefore, markers of the

level of activity of a disorder, if available, are

particularly suitable as tools for therapeutic monitor-

ing. Indirect measures of disease activity, such as

organ functional state or metabolic status, can also

be highly reliable indices when monitoring therapy.

An example is monitoring the reticulocyte count to

evaluate the effect of treatment of iron deficiency

anemia with iron. The evidence of successful

therapy is apparent within days when this measure of

marrow generative function is used.

Sometimes neither direct nor indirect laboratory

markers of disease activity are available. In such a

circumstance, it may be possible to use a measure of

therapeutic intensity as a predictor of therapeutic

response. This situation arises not infrequently in

drug therapy, especially with drugs that are used to

control episodic clinical conditions such as epilepsy.

This kind of monitoring, called therapeutic drug

monitoring, is discussed in a later chapter.

Timing of monitoring studies

Therapeutic monitoring using direct or indirect

measures of disease activity should be performed at

those times following the institution of therapy that

most reliably indicate the response of the marker to

the therapy. For the example of monitoring iron

therapy in iron deficiency anemia, if one uses the

reticulocyte count, the maximal response is seen

days after beginning therapy so this is the best time

to perform the study. If one uses the blood

hemoglobin concentration to monitor iron therapy, a

3 mmol/L (2 g/dl) increment requires approximately

3 weeks, so monitoring with this criterion calls for a

study at 3 weeks. If the restoration of a normal

hemoglobin concentration is the monitoring

criterion, a hemoglobin determination should be

performed at 6 weeks. Individually none of these

monitoring schemes is fully satisfactory. If one

looks only for an initial reticulocyte response to iron

therapy, later evidence of coexistent vitamin

deficiency or other complicating factors will be

missed entirely. If one only looks for the final resto-

ration of a normal hemoglobin concentration, one

will miss early evidence of an incorrect diagnosis of

iron deficiency. The optimal monitoring strategy

here, and generally, consists of a combination of

monitoring studies; rapidly responsive markers

measured early on to assess the immediate impact of

therapy and definitive markers measured after the

new physiologic steady-state is achieved to deter-

mine if that steady-state is the one expected in

response to therapy. If therapy is meant to maintain

an altered physiologic state for an extended time,

periodic monitoring of the state is also desirable.

The timing and frequency of periodic monitoring

depends upon many considerations including the

therapeutic schedule, the time course of marker

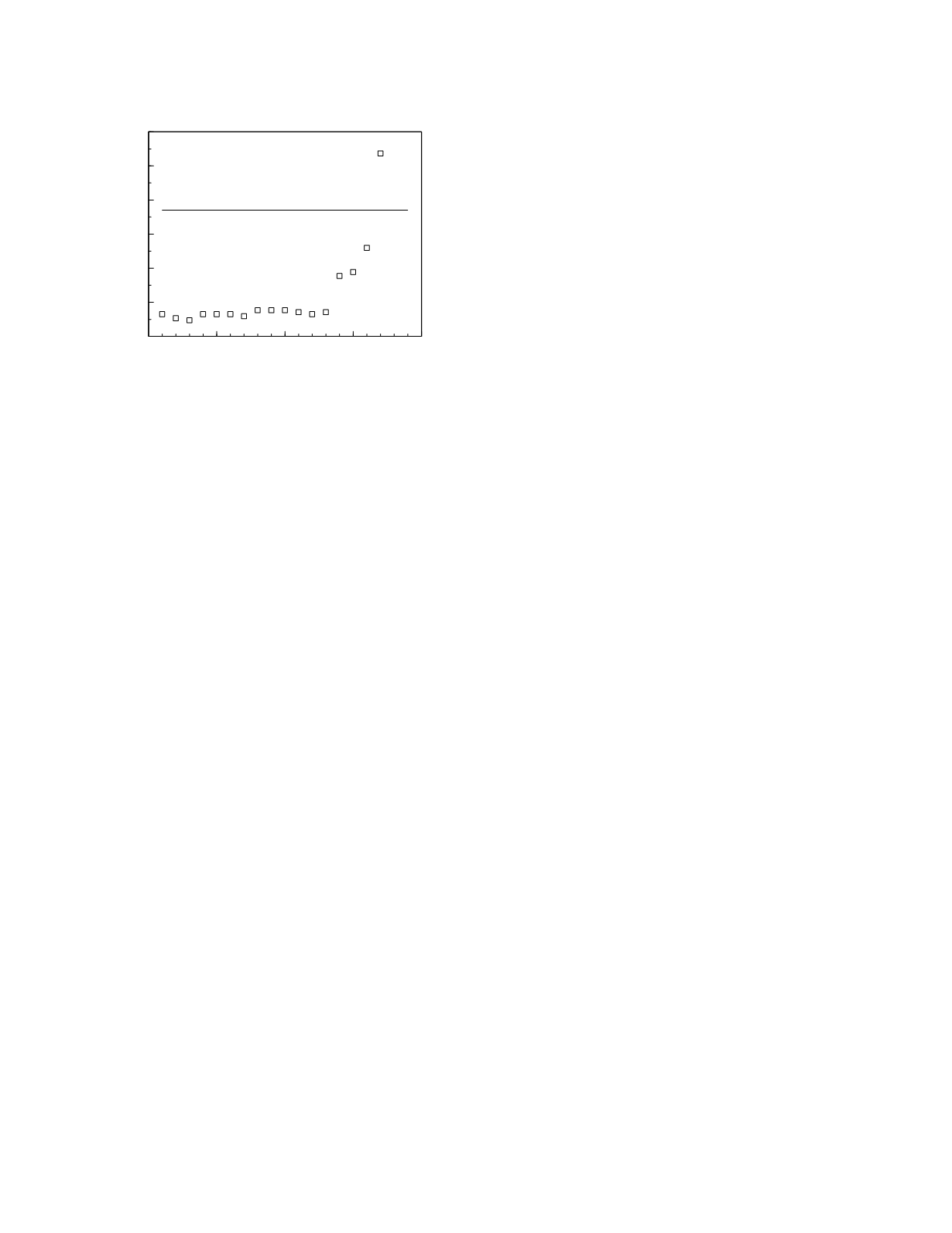

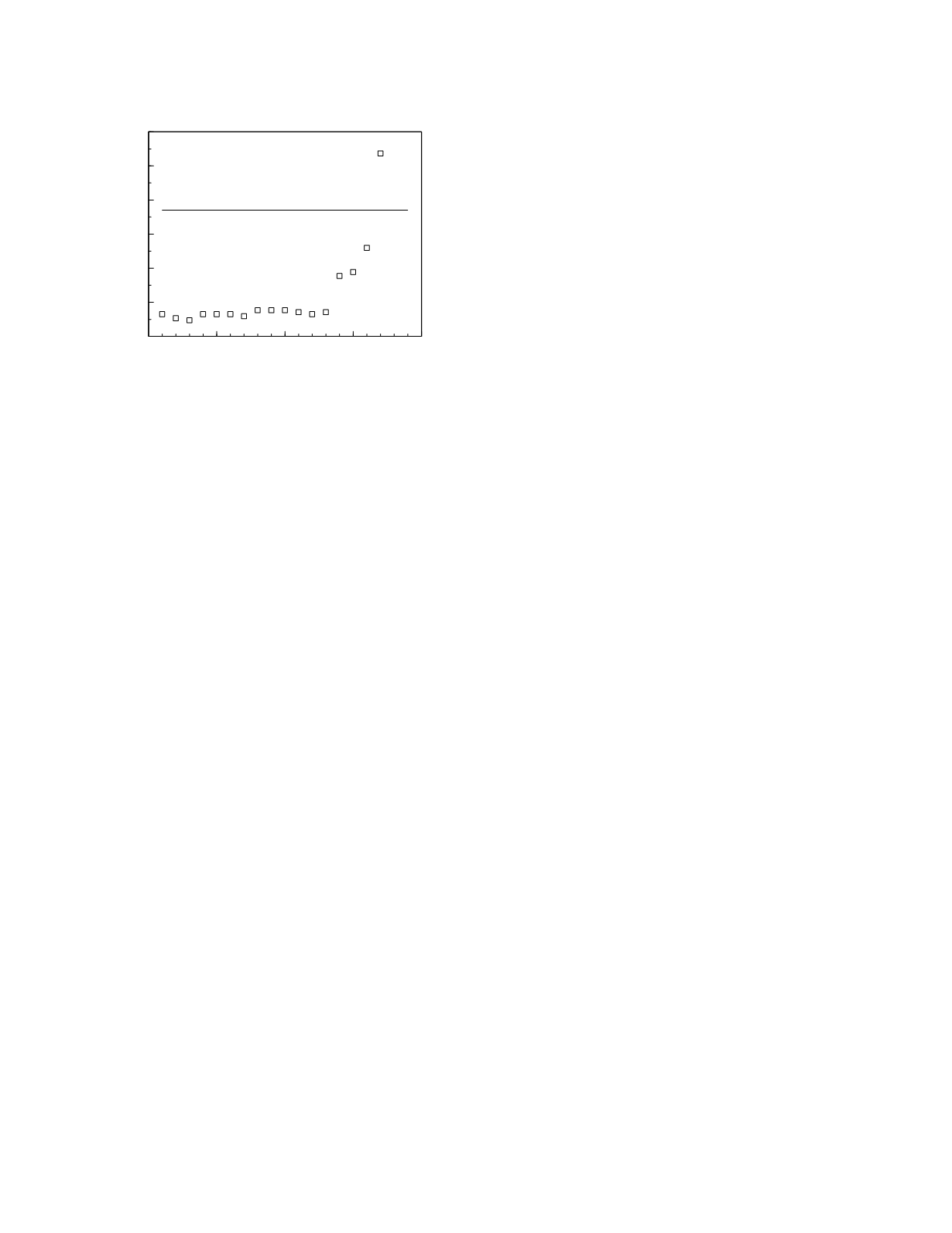

Monitoring

5-8

0

5

10

15

20

Time (months)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

CEA (µg/L)

population-based

critical value

Figure 5.6

Postoperative plasma CEA concentrations in a

patient with breast cancer. Data from Winkel

et al.

(1982).